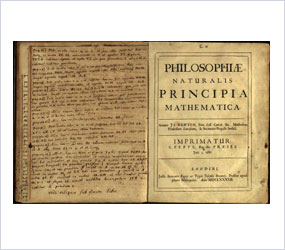

Jacqui Grainger, Manager of Rare Books & Special Collections at the University of Sydney, speaks to Librarian Insider to share a fascinating insight into how the University of Sydney Library came to hold an annotated copy of the first edition of Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, or Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy.

The University of Sydney Library holds an annotated copy of the first edition of Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, or Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. In the Principia, Newton revolutionized mathematics and physics, stating his laws of motion and universal gravitation, and formulating classical mechanics and a derivation from Kepler of the laws of planetary motion. The Principia was first published in Latin in 1687, a century before the First Fleet landed in Sydney with its cargo of convicts, marines and civil servants. How did a rare copy of the Principia find its way there?

The modest-looking volume was donated, in December 1961, by Miss Barbara Bruce Smith of Bowral, New South Wales. It had been a treasured possession of her father, the Hon. Arthur Bruce Smith, a barrister and King’s Counsel, who had been a member of both the New South Wales and Federal parliaments, and who had assisted in drafting the Australian Federal Constitution. Bruce Smith had acquired this copy of the Principia from a Sydney resident, Mr H C Elderton , in a collection made up largely of law books. Elderton had received it as part of property that had been held in Chancery, a court of equity in England and Wales, which was notoriously central to Charles Dickens’ novel Bleak House. Prior to this, it had belonged to the family of James of Ightham Court, Kent, and was stored there with other books in oak chests – probably forgotten – until their despatch to Australia.

The Principia’s third book, De mundi systemate or “On the system of the world”, considered the consequences of gravity and consequently astronomy, the motion of the Moon and marine tides. His “Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy” postulated empiricism – collecting, recording and analysing data. In this work, Newton produced “the ultimate exemplar of science” (G E Smith 2008 "Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica" The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy E N Zalta ed.). The establishment of a colony in New South Wales was politically expedient because of the loss of the profitable American colonies run on convict labor, and the resulting overcrowding in the prisons. How much, we can speculate, of the means of expedition, discovery and navigation that made this possible, was enabled through the work of Newton and his influence on the world of science and its applications?

First editions of the Principia are rare, and the one in Sydney even more so, because it is one of very few annotated copies in existence (some of its annotations were used in editing the second edition). In 1908, when owned by Bruce Smith, it was believed that this copy had been given by Newton to the Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier for editing. This was still the case in 1953, as included in “A Census of the Owners of the 1687 First Editions of Newton’s ‘Principia’“, published in Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 47. Inside the front and back boards, the endpapers and blank leaves – nearly five pages in total – are annotated in Latin. Throughout the book there are also additional annotations and alterations to diagrams made in two other hands: Roger Cotes’s and Newton’s. The task of re-editing had not been completed, and was taken on by Roger Cotes, who from 1709 was a young and distinguished Plumian Professor of Mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge. Cotes’s annotations run throughout the text, and his hand was identified in 1908 for Bruce Smith by Walter Grey, librarian of Trinity College. The diagram amendments were made by Newton himself. A letter published in Nature, in July 1908, by Professor J Bosscha of Haarlem, Holland, stated that the manuscript corrections by Fatio were well known, and formed the subject of correspondence between Fatio and Huygens, a prominent Dutch mathematician and scientist, in 1691. However, the Bodleian Library holds a copy inscribed by Fatio, and by 1973, Bernard Cohen, Professor of the History of Science at Harvard, identified the hand to be that of the Scottish mathematician John Craig, who was well known to Newton.

There are potentially eight other known copies of the first edition of the Principia with annotations in Newton’s hand:

- Trinity College Library, Cambridge – three copies. One with notes and corrections; a second, given to John Locke by Newton, with some corrections; and a third, Newton’s own copy, with manuscript notes.

- University Library, Cambridge – Newton’s own copy, interleaved and copiously annotated.

- The Huntingdon Library, San Marino, CA, on permanent loan from Babson College Library, the Grace G Babson Newton Collection, Massachusetts – three copies. One, on p323, has an inserted slip of paper with writing in Latin giving directions for the omission, in the second edition, of Corollaries 6-9, proposition XXXIII, and for all of Proposition XXXIV; a second, marginal notes ascribed to Newton; and a third, an annotated copy acquired in 1978, with corrections by Edmond Halley, astronomer, mathematician and physicist, as well as Newton – this one also surfaced in New South Wales (the University of Sydney has a file of correspondence between its former owner and various members of the University of Sydney, before purchase by Babson College).

- The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin holds two first-edition copies, one with manuscript additions and corrections.

Craig’s annotation on the subject of motion in resisting mediums for the building of ships was incorporated into the re-edits for the second edition, and Craig took his place as a contributing editor alongside Newton’s major editors Roger Cotes, Edmond Halley and Henry Pemberton. Newton also gave a copy to John Locke. Inscriptions in other copies illustrate their ownership by illustrious contemporaries: Samuel Pepys, Richard Bentley, aristocrats such as the first Duke of Devonshire and senior clergy such as John Moore, Bishop of Ely – all concerned with being knowledgeable and informed, all influential and leaders in their fields. The copy of the Principia at the University of Sydney provides a fascinating insight into the history and processes of peer review in academia and re-editing for subsequent publications, and illustrates one means of the transmission of ideas in the late 17th and 18th centuries.